More than 250 scientists from twenty-five countries gathered in Knoxville on August 4-10, either in person or virtually, for the inaugural Global Amphibian and Reptile Disease Conference. Pioneering research on amphibian diseases conducted through the Center for Wildlife Health at the UT Institute of Agriculture resulted in Knoxville’s selection as host city for the seven-day conference.

The conference included seven workshops and 149 scientific presentations. Topics ranged from herpetofauna and One Health to mathematical modeling of amphibian and reptile diseases to the importance of accessibility in science. Research field trips, social events, and evening activities for participants were also offered.

Students, scientists, veterinarians, and natural resource practitioners were among conference participants, as were policy makers and other stakeholders. Despite their diverse backgrounds, individuals at the event were united in the goal of using the conference as a springboard to find solutions to emerging infectious diseases that are plaguing global amphibian and reptile populations, and to help set the agenda for their research for decades to come.

Prominent among the conference’s twenty-one sponsors were the National Science Foundation, Deutsche Gesellschaft fur Herpetologie und Terrarienkunde, Environment, Climate Change Canada, Morris Animal Foundation, Wildlife Disease Association, Amphibian Survival Alliance, US Geological Survey, and the Association of Zoos and Aquariums.

Matt Gray, professor in the Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries, and other organizers successfully raised more than $85,000 to increase diversity, equity, and inclusion at the conference. The funds supported participation by students and early career professionals from five continents. In total, organizers were able to provide forty-four travel grants to participants from nine countries and thirteen US states.

Gray says organizers accomplished their goal of fostering discussions among researchers on various amphibian and reptile disease threats. They also fostered unity among globally dispersed scientists and students, he adds.

“To me, the most impressive outcome of this inaugural conference was its inclusive atmosphere. More than half of the presentations were delivered by students, and they frequently engaged in discussions without inhibition. It was inspiring to see the next generation of scientists enthusiastic about solving the complexities of global emerging herpetofaunal diseases. Our hope is that the knowledge participants took away about the similarities and differences among host-pathogen systems and disease management strategies will help set research agendas and foster conservation of herpetofauna species for years to come.”

Positive impacts are needed, starting with recognizing that biodiversity matters. Biodiversity is the foundation of a healthy planet and a One Health approach is necessary to achieve planetary health. When pathogen infection causes disease, populations of amphibians and reptiles can be reduced, and even species extinctions could occur. Such losses threaten to unleash a chain of consequences, and not one of them is good. Reptiles and amphibians are important food sources for various birds and mammals, and frogs, toads, and lizards are important consumers of insects—many of which are agricultural pests or, in the case of mosquitoes and ticks, carry and transmit zoonotic diseases. The loss of amphibians or reptiles from an ecosystem can have cascading effects that influence natural processes such as nutrient cycling and climate change, and also can negatively impact human health.

“Human, animal, plant, and ecosystem health are interconnected; the health of one is impacted by and also impacts the health of the others. From a One Health perspective, it’s hard to predict all the consequences that loss of populations of specific amphibians and reptiles could have,” says Deb Miller, UT professor of wildlife health and director of the UT One Health Initiative. “What we do know is that high-concern diseases such as snake fungal disease, pond turtle shell disease, ranaviral disease, and chytridiomycosis have already resulted in die-off events and, in some cases, extinction of herpetofauna species across the world.”

The loss of amphibians or reptiles from an ecosystem can have cascading effects that influence natural processes such as nutrient cycling and climate change, and also can negatively impact human health.

Diverse factors causing diseases to emerge in amphibians and reptiles include changes to the environment that negatively affect the health of species and give pathogens an advantage over their immune systems. Humans also affect host-pathogen interactions by unnaturally transporting pathogens long geographic distances during international trade or on footwear and other gear when traveling abroad.

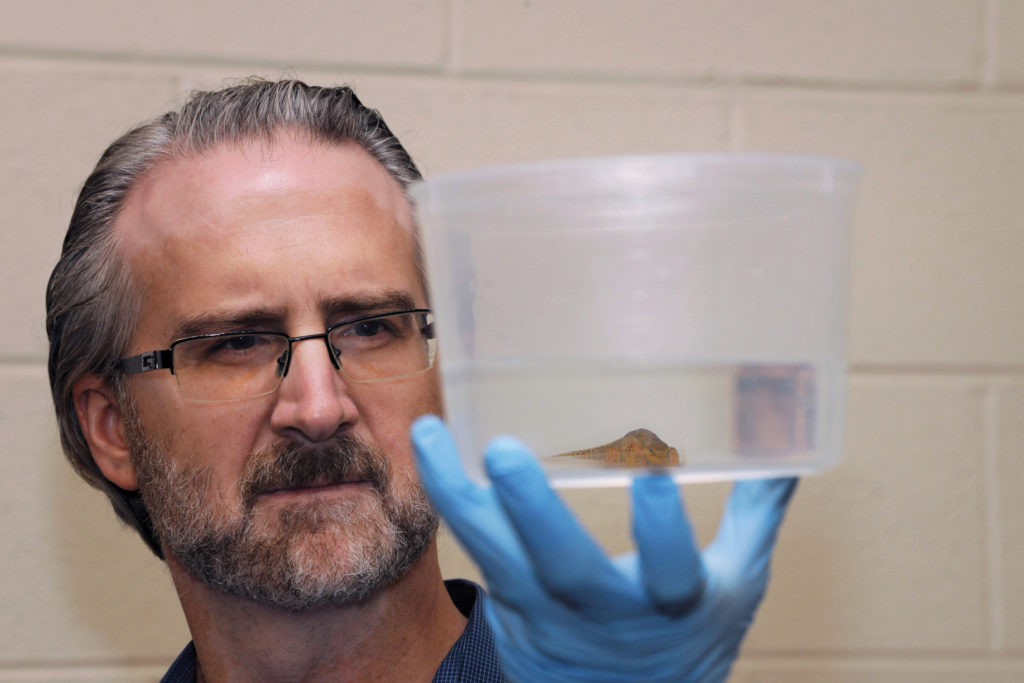

Gray and the UTIA team along with collaborators at four other institutions have for years engaged in basic and field science to characterize environmental threats to amphibians. Now their studies are branching in a new direction.

In August 2022, three federal agencies awarded a $2.75 million grant to a UT-led team to conduct a study that will identify and assess how pet amphibian trade networks may amplify pathogens. United in funding the project are the National Science Federation, the National Institutes of Health, and the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture. The project leadership reflects the teamwork and strength of UTIA and UT Knoxville, with principal investigators being Gray; Neelam Poudyal, a professor of natural resource policy and human dimensions in the Department of Forestry, Wildlife and Fisheries; and Nina Fefferman, professor in the Department of Math and Department of Ecological and Evolutionary Biology, and also director of the National Institute for Mathematical and Biological Synthesis (NIMBioS.org) and associate director of the UT One Health Initiative. Project collaborators include scientists at Washington State University, Michigan State University, University of Massachusetts, and Rutgers University. The Pet Advocacy Network also is an important partner.

Gray says that the knowledge the team develops will increase understanding of factors that contribute to the movement and persistence of pathogens in amphibian trade networks, as well as those of other wildlife. Foundational work for this project was supported by a seed grant from the UT One Health Initiative, which helps facilitate research and other projects among faculty, students, and the public across the UT System’s statewide network of universities, institutes, and centers.

Explore More on

Features

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE