Rolling hills dotted with green barns and buildings. Wide open pastures teeming with cattle and calves. The roof of a shed decorated with a newly painted, eighty-foot-wide “Everywhere You Look, UT” mural.

This is Johnson Farm, the latest location in UT System’s statewide mural campaign.

Those who know owners Rena and her late husband Bill Johnson don’t need proof of their UT pride. But for the 2,907 other daily travelers passing by the farm on Roberts-Matthews Highway in White County, the campaign’s thirtieth mural commemorates a family deeply rooted in both UT and agriculture.

When Rena transferred to UT Knoxville in 1958, she received one piece of advice: don’t date the football players.

That person must not have known Bill.

Bill was a UT Knoxville football standout: co-captain of the 1957 team, All-SEC guard, and the school’s first All-American and Academic All-American. But he was also an Army ROTC battalion commander, a Torchbearer Award recipient, and, more importantly to Rena, a Sunday school teacher and a humble young man from Middle Tennessee.

The pair were first introduced at a UT Knoxville athletics event when Rena was a sophomore at Randolph-Macon College in Virginia–and dating a different UT Knoxville athlete. After Rena transferred, Bill seemed to be an unavoidable fixture in her life, both because of their chance run-ins and the pleas from her brother, who knew Bill through ROTC and class, to date him. One rainy day, Rena and Bill ran into each other outside of the business building. Their conversation amidst the downpour resulted in their first date.

That initial piece of advice never stood a chance.

Soon after they married in 1959, the couple returned to Bill’s hometown of Sparta. But the love grown at UT Knoxville—for each other and the University—would stay with them for the rest of their lives.

Bill had several great loves in his life: faith, family, his banking career, UT football, and the farm. Bill’s grandfather bought the land in 1893 and passed it on to Bill’s father. Much of Bill’s childhood was spent on the farm, helping to slaughter hogs, cure tobacco, or tend to calves. When his father passed away shortly after Bill and Rena returned home, Bill was the only Johnson left to take over the farm. Its fate was in his hands.

“Dad felt this debt to the University that he could never repay. That no amount of money or service he could ever give would equate to the education he received, the opportunity to play football, his lifelong friends, and his experiences.”

“I don’t think there was ever a question of keeping it or letting it go,” Rena says. “Bill always knew he would go back to the farm because it was his heritage.”

Today, the farm is a Century Farm—a designation given to farms owned by the same family for at least a hundred years. The farm has seen a lot of change in its 130 years, including the addition of around 350 acres to the departure of all operations but cattle. Rena now operates as “farm manager”—a title she insists she assumed as a joke after Bill’s passing—and leases out the land to two local farmers.

One thing that has never changed is the farm’s status as a working farm. The Johnsons’ three daughters can attest to that.

“I can remember dad coming home from work, coming from the bank with his nice clothes on, to see that we weren’t hauling hay as fast as he wanted,” says Cathryn Rolfe, one of the Johnsons’ three daughters. “He would jump up on the tractor with his tie on and kick it into high gear.”

“It was a point of pride for my dad that his girls worked on the farm,” says Rolfe. “He loved the fact that his daughters could pull their own weight.”

Life lessons prove unavoidable on a farm, and the girls learned plenty of them: responsibility, appreciation for farmers, flexibility, the importance of family, priorities, an obsession with checking the weather. Once, in high school, Rolfe showed up to her basketball game late and with muddy shoes because she had to tend to a cow that got out while she was home alone. Instances like that weren’t rare—they just came with the territory.

“The farm was an essential part of our lives,” says Carolyn Bronson, the Johnsons’ youngest daughter. “We understood the importance of our land and what that meant in a broader sense.”

“It’s like our touchstone,” echoes Cynthea Amason, the eldest Johnson daughter. “I can really sense my place in the continuous flow of my family here.”

As the farm taught them lessons about life, their parents taught them lessons about love—for each other, for others, for UT.

Rena and Bill lived by the motto, “It is better to give than to receive.” They spent their lives quietly embodying that phrase by giving their time and money to others, whether by donating farm equipment to local schools, establishing endowments at UT, or one of the countless other acts of generosity towards strangers and friends alike that often weren’t publicized.

“My mom and dad taught us how to approach life,” says Rolfe. “We knew that to whom much is given, much is expected.”

That’s one reason the Johnsons were such strong advocates for their alma mater.

“Dad felt this debt to the University that he could never repay,” said Amason. “That no amount of money or service he could ever give would equate to the education he received, the opportunity to play football, his lifelong friends, and his experiences.”

Rena and Bill’s support of UT extended well beyond their college years, with Bill serving as a member of the UT Board of Trustees, among other leadership roles, later in life. The couple’s sentiment didn’t go unnoticed—all three of their daughters are also UT Knoxville graduates.

“Our connection to the farm, that history and what it stems from, mirrors our connection to UT,” says Rolfe. “Those two things are very integral to all our lives.”

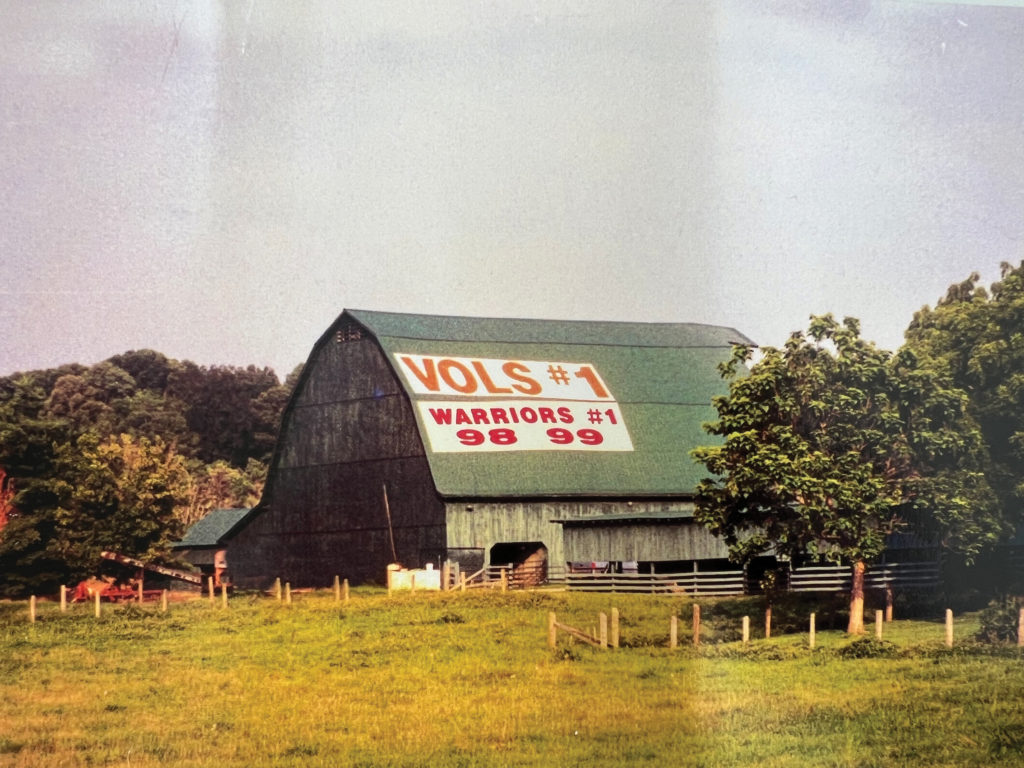

When Rena first heard about the “Everywhere You Look, UT” mural campaign, she knew two things: that a mural needed to be on her farm, and that she knew exactly where she’d put it. Ever since it was built in the 1930s, the big green barn had been a landmark for the family, the farm, and the community. It was the perfect place for a UT System mural.

“When people saw the barn, it was like coming home,” says Rena.

When a 2021 tornado tore down the barn and her mural plan, she re-strategized—an activity in which farm life has made her adept. The old cattle shed twenty-five feet from the original barn would be just as good. Any place on the Johnson Farm would be, really.

“Having one of these murals just seemed like the natural thing for us to do,” said Rena. “Bill would be so excited to see it, I think he’d even forget that the barn is gone.”

Explore More on

Features

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE