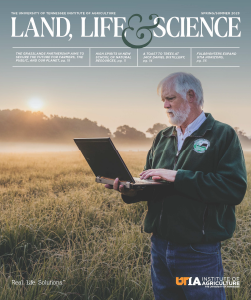

Pat Keyser has made his career studying and educating farmers about native grasses. As director of the UT Center for Native Grasslands, Keyser leads research focused on the management of native grass-based production systems including forages and biofuels, management of grasslands, and restoration of grassland communities. So, it’s little surprise when Keyser shares his opinion that the profit driver of beef cattle operations is not, in fact, cattle, although their sales support the operations. The real driver is the grass whose consumption supports the cattle.

Forbes Walker, a soil science professor and Extension specialist, takes that a step further. For Walker, the profit driver of cattle operations are the healthy soils—those with high organic matter, good aggregate stability, and low bulk density—on which grass grows.

Vigorous grasses and healthy soils are at the heart of just-launched work on a USDA-funded climate-smart grant led by Keyser and involving Walker and other UTIA experts. The grant is one of seventy climate-smart commodities partnership grants the USDA awarded last fall in the first pool of grants in Climate-Smart Commodities, for which $2.8 billion has been allocated. The agency is funding pilot projects that promise to expand markets for US farms, including those of small and underserved producers, who grow commodities that reduce greenhouse gas footprints, increase carbon sequestration, and provide meaningful benefits to production.

The grant that Keyser, Walker, and a multidisciplinary, multi-institution team of Extension specialists and scientists landed is funded at $30 million for research and Extension across the next five years. Their project, titled “Climate-Smart Grasslands—the Root of Agricultural Carbon Markets,” focuses on a nine-state region that represents the core of grassland agriculture for the eastern United States. The goal is to prepare grassland farmers to enter the carbon economy while enhancing operation resiliency and optimizing profitability, soil health, and biodiversity—scenarios in which everyone benefits.

Grasslands constitute the single largest land use in the US, as well as agriculture’s largest and most effective carbon-storage system. Grasses, particularly those being judiciously grazed, remove large volumes of carbon from the atmosphere and store it in the ground within their extensive roots.

The UTIA-led partnership is impressive. Members of the team represent more than thirteen land-grant institutions, four conservation groups and four industry organizations, six trade associations, and three state agencies (see the end of the article for the full roster).

The largest number to know—and the most important—is 230. That is the number of farms sited across the nine states that will implement one or more of six sustainable agricultural practices under evaluation to provide real-world insight and data on their effectiveness.

If vigorous grasses and healthy soils are at the heart of the project, participation by the 230 farms is the heartbeat that will keep everything pumping. The farmers’ involvement is front and center to the work because the demonstrations they host on their land will be measured and analyzed to obtain data on impacts the practices make to the soil, including increases in the amount of carbon the soil sequesters.

The large number of farms allows robust monitoring and verification of the practices that will yield proven, thoroughly documented results from a large-scale, geographically diverse region. To date, there has been a lack of such real-world evaluations of the benefits of conservation practices for improving soil carbon storage, particularly carbon stored deep within the soil. This lack of certainty leaves the whole carbon marketplace on shaky ground. And, in turn, that keeps investors, and farmers, on the sidelines.

Establishing Tight Teamwork

Although the climate smart grant award was announced in September 2022, funding still had yet to be awarded in February 2023, something that didn’t surprise Keyser. “There are always lots of details to work out on these federal grants and loose ends to tie before everything is settled,” he says. But February was not too early to get the project underway, and that was precisely what happened at a day of organizational meetings held February 28 in a UTIA conference room overlooking Brehm Animal Science Arena.

Twenty-six people were present for the meetings, key players among the thirty-two organizational partners of the project. An around-the-room introduction included titles such as state forage specialist, smallholder farm agent, soil scientist, agricultural economist, and project manager. Also present were a UTIA postdoctoral scientist from Rwanda and two Herbert College of Agriculture PhD students: one from the School of Natural Resources and the other the Department of Biosystems Engineering and Soil Science. Student involvement will continue to grow as the project proceeds.

Keyser, who speaks in a deep bass, told the gathering that he wasn’t there to preach to the choir. Everyone knows the tasks that lie ahead, he said. “The goal is for us to be doing the same thing in the same way so we can implement practices in a consistent manner across this large region.”

Keyser says he was pleased with how the kickoff meetings went. “Any time you have such a large—and experienced— team all together in one place, you wonder where you will land at the end. Built on the common vision we all shared for this work, for improving the stewardship of our grasslands and the farms that supports, I guess I was not surprised that we landed right on the bull’s-eye. Folks left that room with a very clear sense of purpose, of what this partnership needs to do to put our grass farmers in a position to be competitive in the agricultural marketplace unfolding before us.”

Partnership is a word about which Keyser is firm. “I’m with UT, and the grant was awarded in response to the proposal we submitted, but this is truly a partner-led effort. We call it the ‘Grasslands Partnership,’ and our brand statement is ‘Conserving our soils, farms, and environment.’”

The Many Ways to Say Best Practices

Although the USDA’s name for this program is “climate-smart commodities,” many of the underlying approaches may sound familiar to farmers. Some in the past have referred to many of these practices as “regenerative,” yet that term is vague and could mean different things to different people. Likewise, some may want to call this sustainable agriculture, and it certainly does contribute to improved sustainability of all sorts of things—soil, wildlife, and farms themselves. But regardless of labels, the whole endeavor comes down to best practices: practices that reduce inputs, store more carbon in the ground, and improve profit margins for the farm.

Specifically, this project will evaluate tools that hold the greatest promise for meeting all of these goals:

- Integrating deep-rooted, low input native grass pastures into existing forage programs.

- Using organic sources of nitrogen—poultry litter, clovers—rather than energy-intensive sources such as urea.

- Improving grazing management to ensure vigorous pastures with well developed root systems.

- Implementing silvopasture, a practice that plants a small number of tress within pastures, resulting in more shade for cattle, alternative revenue streams for the farmer, and greater storage of carbon in the soil as well as in the aboveground portion of the trees.

- Using novel soil amendments such as biochar and gypsum that have been demonstrated to increase soil carbon storage and at greater soil depths.

- Adding perennial grass field buffers on marginal cropland: a means of increasing soil carbon storage, reducing runoff, and improving habitat for pollinators and wildlife, including species such as bobwhite quail.

A Viable Path to Carbon Markets

There’s another layer to the project, and it is an exciting one and future focused. The project will enable scientists to unlock many practical solutions and strategies that take advantage of the incredibly complex world that thrives out of sight, within the soil that lies below a well-managed grassland. Their objective is to gain new understanding of exactly how farmers can implement profitable strategies that not only produce forage and beef, but also allow them to increase carbon storage in the soil and reduce energy-intensive inputs that contribute to greenhouse gases. Careful measurement of these gains across the five years of this project will enable the scientists to validate the specific outcomes and develop algorithms that calculate the benefits—down to each field.

The measurement and validation of those benefits, in turn, will position grassland farmers across the Southeast to take advantage of emerging agricultural markets, markets that promise to value more “climate smart” agricultural products. One way that can happen is through carbon credits. According to Ecosystem Marketplace estimates, the total carbon offsets market was worth $2 billion in 2021. Boeing was among the buyers, as was Lyft. They and others tend to contract with large-scale operations, including farmers, for carbon credits to support goals for carbon neutrality of their operations.

Southeastern farmers face several challenges to enter these carbon markets. One is that most are much smaller than the large operations already selling in the markets, making transactions more numerous and less efficient to buyers seeking large amounts of carbon. Another challenge is the lack of reliable estimates of how much carbon they have on their farms, how those carbon pools change over time, and how they respond to various management practices. This lack of sound data makes the whole carbon marketplace very uncertain to both sellers and buyers alike. Developing the models based on real world, on-farm data, will help establish much more transparency for these markets.

Finally, there needs to be a way to connect buyers and sellers to make contracting both easy and attractive. This facet of the grant project involves Seong-Hoon Cho, a natural resource and environmental economics professor in the UT Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics.

Cho is working to assemble what he calls the “Zillow of Carbon Markets.” Homebuyers know Zillow. When searching for a home, you pull up the Zillow website, enter some search criteria, like desired zip code and house size, and Zillow shows you photos and information of residences that might be of interest. Cho sees the same system as key to contracting with smaller farms for carbon credits, including even bundling smaller farm properties into a larger entity, with which a contract can easily be made for a large number of credits. Achieving this will put small farms on closer to equal footing with farms far larger in scale and provide the smaller farms of the Southeast with more direct access to markets

“The web app will create an intuitive online tool that provides the essential information about carbon credits by identifying a reasonable minimum acceptance price given costs associated with implementation of climate-smart practices,” Cho explains. “The minimum acceptance price for the carbon credit will be similar to a real estate property sellers’ listing price that initiates their sales transaction.”

The core of the web app will be the ability to capture the value of the positive externality grassland farmers create within a market system. Cho and the team hope this will enable farmers to optimize economic decisions and to negotiate with science-backed carbon credit estimates.

The Timeline

The timeline of project key steps includes:

Spring 2023—Complete contracts with the USDA and partners

Summer 2023—Develop team of Extension agents across all nine states

Fall 2023—Identify collaborating farms to validate and demonstrate proposed practices

Spring 2024—Implement on-farm practices

2024-2028—Conduct intensive monitoring of on-farm practices and outreach across the farm community

2028-2029—Complete analyses and develop models to facilitate markets for farmers

Keyser says, “As the prospects for an agricultural ‘carbon economy’ become more likely, this partnership will position our grass farmers to take full advantage of that opportunity through improved grasslands stewardship that also benefits our environment—from soil health to at-risk grassland birds and pollinator populations.” And those are outcomes that are clear wins for everyone.

Grasslands Partnership Members

University of Tennessee, Tennessee State University, University of Arkansas, Alabama Cooperative Extension, University of Kentucky, University of Missouri, Clemson University, North Carolina State University, Purdue University, Virginia State University, Virginia Tech, Tyson Foods, Inc., JBS Foods, Corteva, Farm Credit Mid-America, Ecosystem Services Marketing Consortium, American Forage and Grassland Council, National Grazing Lands Coalition, National Cattlemen’s Beef Association, US Roundtable for Sustainable Beef, Multiple state cattle associations, American and Tennessee Farm Bureau Federations, The Nature Conservancy, American Bird Conservancy, Monarch Joint Venture, National Bobwhite Conservation Initiative, Tennessee Department of Agriculture, Missouri Department of Conservation, Virginia Department of Conservation and Recreation

Explore More on

Cover Articles

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE