Doctoral Student Leads Ash Tree Study in the Great Smoky Mountains

Invasive pests and pathogens, arriving in the United States through global trade and travel and sometimes even borne on the wind itself, are waging a war on trees across the nation. The destruction is at a level that it is putting native ecosystems at risk.

Perhaps the direst case today is the plight of ash trees, which are under threat of extinction by the emerald ash borer, a green buprestid (or jewel beetle) native to northeastern Asia. This beetle is known to cause up to 99.99 percent mortality among nearly all affected native ash species and has spread rapidly across the eastern US since its initial discovery near Detroit, Michigan, in 2002

Zane Smith, a PhD student in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology, a part of the Herbert College of Agriculture, is spearheading research on native ash trees in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park to inform the conservation and restoration of our native ash species.

Smith is one of eight UT Knoxville students to receive the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship award. The Herbert College of Agriculture student’s fellowship study is to use genomics to assess ash tree biodiversity, hybridization, and local adaptation. As a fellowship recipient, Smith is now receiving $147,000 in financial support to continue his research and protect ash trees from extinction. Smith says, “It’s an incredible opportunity that I cannot begin to express my gratitude for.”

The Journey to Tree Conservation

Smith readily admits that he wasn’t always a “tree person.” Originally from Knoxville, he completed his undergraduate degree in modern foreign languages at UT Knoxville in 2013. After graduation, he joined his family’s business, a local produce market and garden center. Then he decided to return to UT in 2020 to pursue a newfound passion for botany.

Smith says he found his passion through working with native species and local growers for stock for his family’s garden center. “The experience led me to fall head-over-heels in love with plants,” he says. This time at UT, he headed to the Herbert College of Agriculture, where he not only earned a second degree in plant sciences but engaged in undergraduate research alongside entomology and plant pathology associate professors Meg Staton and Denita Hadziabdic Guerry.

Over time, Smith fell in love with tree conservation because of his undergraduate research experience in tree genetics and his position as a student assistant at the Hesler Biology greenhouses. He thought, “If I want to make the biggest impact working in plant conservation, where should I target my studies?” Forest research was an obvious choice for an aspiring conservationist due to its broad impact on both native ecosystems and society.

“As a child, I spent countless hours in the Great Smoky Mountains, tucked away under the forest canopy. This project is really a love letter to the land I grew up on.”

-Zane Smith, Herbert Graduate Student

Why Ash Trees?

When asked, “Why ash trees?” for a research project, Smith says it boils down to applying his passion for conservation to a dire need.

Smith elaborates, “Trees are somewhat unique in that they both compete to survive in and of themselves, while also creating unique ecosystems by virtue of their size and complex form—both above and below ground. Truly, trees are habitat and provide food, shelter, and ecological stability at an ecosystem scale within forests.”

He continues, “By conserving trees, we improve conservation action for forest-dwelling understory plants, animals, fungi, insects, and all manner of other organisms.” In other words, protecting trees from extinction is essential to preserving the ecosystem on which we depend.

For ash trees specifically, a vast majority are in danger because of the emerald ash borer, and Smith says the existing ash trees create a unique opportunity to characterize and preserve the genetic diversity that still exists. Ash tree populations are deteriorating, yet there are still enough to assess their existing diversity and construct restoration plans to ensure these species’ survival.

The Smokies and Beyond

While several species of ash can be found across more than half of North America, Smith’s research focuses on the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, which is primarily home to green and white ash. There, Smith and a team of undergraduate research students from UT have been gathering samples to study how environmental and genomic data can be integrated to better understand their ecological and evolutionary dynamics.

Smith and his collaborators seek to answer questions such as, “How are these trees adapted to the unique mountain climates of the Great Smoky Mountains?” and “How do these trees share adaptive traits that impact the long-term survival of populations?” The data generated by this project will also be useful for examining signatures of genetic resistance to the emerald ash borer in local populations once resistance is better understood.

“The Great Smoky Mountains National Park is a UNESCO World Heritage Site and biodiversity hotspot, so understanding the tree diversity that we stand to lose to the emerald ash borer and other invasive forest pests is a key concern for local conservation efforts—not only of ash—but of other emblematic native trees, such as the eastern hemlock,” Smith explains.

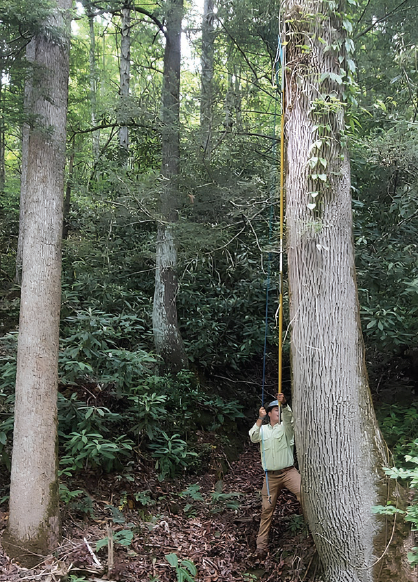

Smith describes fieldwork as “a bit like playing hide and seek.” He and the research team drove and hiked several hundred miles in the mountains, using preliminary species distribution models and location data from previous forest inventories to target their search for trees in suitable habitats. The team looked for mature trees or what had been mature trees to sample leaves and twigs for identification and DNA extraction.

“There were good days and bad days. On occasion, we would hike for several miles, only to find rotten logs or tiny seedlings,” he says.

Even though the Great Smoky Mountains National Park has lost much of its ash, Smith believes they have captured a “snapshot” of the majority of the genetic makeup of the park’s ash trees. This is due in part to the continued efforts of members of the National Park Service who are treating nearly a thousand ash trees across the park with insecticides. “We are hopeful that these efforts can complement their work to ensure ash has a future in the Smokies,” Smith says.

The Bigger Picture

Smith’s research contributes to a larger project by The Nature Conservancy called, “Tree Species in Peril.” This region-wide restoration breeding effort is being conducted for five of the most endangered tree species in the eastern deciduous forest: American beech, eastern hemlock, and three species of ash.

Each tree species is threatened by one or more invasive forest pests that are spreading throughout the region. This creates a time-sensitive opportunity to build upon prior research on similar systems and implement species-specific monitoring, testing, and breeding at an ecological scale.

To date, the emerald ash borer has claimed more than one hundred million eastern ash trees over the past two decades. “By establishing a baseline for the genetic diversity of ash in our local region—and assessing how they have evolved to thrive in their local environment—we are setting a benchmark both for what we stand to lose, and what we must restore once a source of resistance to emerald ash borer has been found,” Smith explains.

Ultimately, Smith’s work with ash trees will serve the search for answers that are currently unknown, ones that also could help protect other tree species across the country.

A Career in Conservation

Smith says he hopes to channel all that he has learned from this research experience into a meaningful career in plant conservation. “My ultimate goal is to work at a botanic garden with a research program in plant conservation, such as the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew in London.” He feels this project has been the perfect stepping stone for making an impact and setting a foundation for his future career.

Hadziabdic Guerry reiterated the prestige of the National Science Foundation fellowship program supporting Smith’s work, and the doors it opens for him and other students in the Herbert College of Agriculture who would like to pursue research at the undergraduate and graduate level.

“When it comes to mentoring students, you’re giving them the wings to fly, and some students just take off.” Hadziabdic Guerry adds, “It’s amazing to see where Zane can go.”

Thank You, Herbert

Smith is thankful for the faculty and staff in the college, particularly his mentors Staton and Hadziabdic Guerry, who have supported and challenged him, and his labmates and the undergraduate sampling crew composed of Aubrey Horner, Cody Roberts, Eli Thurston, Esmeralda Matarazzo, and David Holdridge. “This work would not have been possible without them! I couldn’t have hoped for a better team to share this project with.”

As a part of his dissertation, Smith plans to complete the research project by graduation in spring 2027 and to submit the team’s findings for publication as early as 2025. With the NSF fellowship, excellent mentors, and a solid team at his back, Smith has everything needed to continue his work toward saving ash trees locally, leading to lasting impacts upon the field of plant research and conservation at a national level.

Explore More on

Features

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE