UT Extension Works With Libraries, Counties, Towns, Businesses, and Other Organizations to Spread Broadband to Rural Tennesseans

The Giles County Public Library sits in the heart of downtown Pulaski, Tennessee. Inside the sage green brick building that was renovated in 2014, tall shelves hold a large selection of books for all ages. On this Wednesday, a few patrons sit in front of computer screens, and one man completes work on his laptop and carefully puts it back in a padded bag before nodding his head goodbye to the librarians working at the circulation desk.

The building’s next-door neighbor is the UT Extension office, its partner in spreading internet access to residents who either don’t have access in their homes, can’t afford a service, or both.

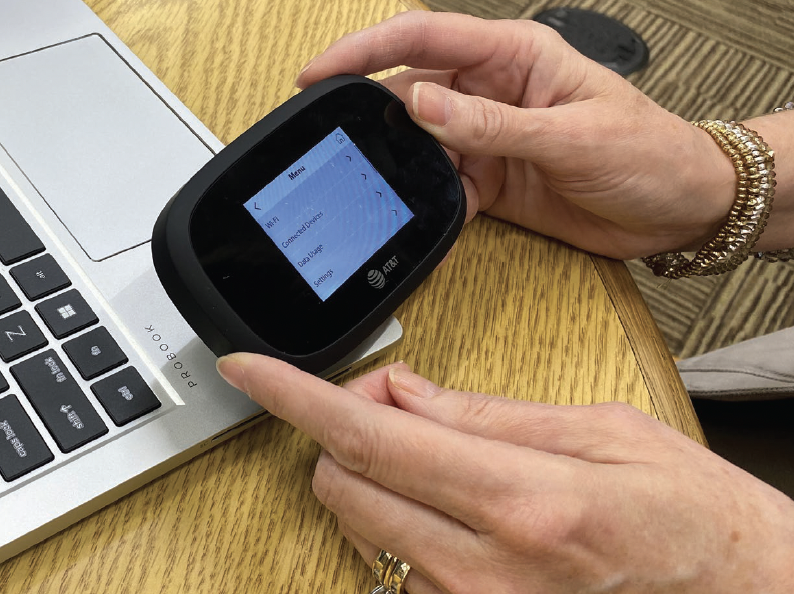

Beyond Second Street in Pulaski, many households surrounded by cornfields or nestled in a shaded hollow do not have a way to receive broadband other than using one of the fourteen hotspot devices borrowed from the library. These hotspots provide a week’s worth of access to the internet using an AT&T or Verizon cell signal, and there is always a waiting list.

Broadband access remains one of the biggest challenges and obstacles for rural Tennesseans. Working with a patchwork of government, university, public libraries, and corporate grants and programs, UT Extension’s Sreedhar Upendram is helping municipalities and counties bridge the digital divide.

“We want every house to be covered,” Upendram says. “The reason kids leave small communities is because they lack opportunities and services, like broadband. We want to level the playing field for those kids.”

-Sreedhar Upendram, UT Extension

Lack of access to broadband is severely limiting for people without it. For those in urban and suburban areas who have broadband service wired into their homes, it seems like an afterthought and even a hardship when service is disrupted for mere minutes or hours. But without constant service, is it very difficult for students to work on their school-supplied laptops at home or for an adult to apply for a job, complete an online degree, or consider working online from home.

“Broadband is essential. It should not be a luxury,” says Upendram, associate professor in the Department of Agricultural and Resource Economics. A statewide community development specialist, Upendram oversees UT Extension’s broadband access initiatives and has an encyclopedic knowledge of grants and programs available from federal and state government and corporations. He’s based in Knoxville but frequently travels to counties near and far, like on this day to deliver two hotspots to the library in Giles County, located along the Tennessee-Alabama border.

The hotspots work by connecting to a cell signal that brings broadband into a home with no internet wiring. Multiple devices can connect at once. The library started with one hotspot in 2015 and added more over time, using the library’s annual fund and various grants. Ten of the current fourteen hotspots in Giles County are part of a multi-county effort funded through a $15,000 University of Tennessee Community Engaged Seed Grant.

“Before the pandemic most people didn’t know we had the hotspot,” says Cindy Nesbitt, library director. “We try to serve the community as best we can. When this opportunity for more hotspots came along, it helped us serve the community even better.”

It’s estimated more than 700 Giles County residents a year participate in the lending program. Some community members drive from as far away as Elkton, about eighteen miles from Pulaski, to pick up a hotspot, she says.

About 60 percent of Tennesseans have access to broadband internet, which refers to a higher speed and capacity necessary to download or upload information. The access issues surrounding remote work and school during the pandemic helped push more funding toward the problem. The federal government provided $14.2 billion for the Affordable Connectivity Program and $42.45 billion for the Broadband Equity, Access, and Deployment Program. For instance, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee and Department of Economic and Community Development Commissioner Stuart McWhorter announced funding of $447 million in 2022 and $185 million in 2023 to help expand access.

The hotspot program is just one of many Upendram oversees through the UT Extension economic development lens. Many programs and individuals across UTIA and the UT System are working to solve this Grand Challenge.

UT Extension Bledsoe County director J.C. Rains and Upendram worked together to secure a $60,000 grant from the Appalachian Regional Commission in 2019 to provide free broadband in downtown Pikeville. Wi-fi service was a hit with people conducting business at farmers markets and festivals. The two conducted surveys on the usage and economic impact.

Upendram and his colleagues worked with Purdue University’s Center for Regional Development to create digital divide profiles for each of Tennessee’s ninety-five counties. As expected, counties in metropolitan areas have broadband infrastructure and residents are more likely to afford a service if it is available, while rural counties scored poorly. In Giles County, as of 2020, 20 percent of households have no internet access, about 12 percent have no computing device, and about 5 percent have no access to high-speed broadband. That is not too bad. Perry County ranks among the lowest in the index, with 74 percent of residents without high-speed broadband, 30 percent with no internet, and 27 percent without a device.

The next step after gaining access is learning how to be digitally literate. Tennessee 4-H trained 400 teens to deliver comprehensive technology education programs for senior adults across Tennessee. This project reached 6,400 adults last year. In fall 2023, the AT&T Foundation announced $100,000 in funding for training workshops in forty-two counties.

Students in 4-H are well suited for this endeavor. They know how to navigate technology better than many adults, and they are able to use their public speaking and presentation skills learned through 4-H to serve the older population and teach them how to use various devices and software.

A collaboration with UT Knoxville faculty in the departments of electrical engineering, civil engineering, and sociology is using a $150,000 grant from the National Science Foundation’s Smart and Connected Communities program to study converging transportation and IT infrastructure surrounding traditionally underrepresented populations.

For people who need an immediate solution—albeit still a Band-Aid—the hotspot program provides it.

Hotspot lending started in Hancock, Wayne, and Bledsoe as pilot programs. It has since been expanded to Cannon, Grundy, Polk, Giles, and Morgan Counties. UT Extension also conducted a pilot study in Bradley County, working with the county commission and school board to provide hotspots to eleven elementary schools.

A key in the program is a paper survey that library patrons complete each time they borrow a hotspot. The data is shared with policymakers to show the impact and demand for more and better broadband service. The survey tracks how residents use the hotspots, where they live, and what they would be willing to pay if service was available.

In Giles County, library patrons can check out a hotspot for one week. There’s a $3 fine for each late day. After three late days, the library turns off the hotspot. Nesbitt says some residents are willing to pay $9 for the extra time, which is far less than subscribing to a service. Upendram’s research has shown the average $50-$70 a month cost for internet service, if available, remains out of reach for many.

Upendram and UT Extension Giles County director Kevin Rose (BS Agriculture Business ’86; MS Extension Education ’96) drove around the county to test internet speeds using cell service to see how the hotspots would work. There were no surprises. “It’s the nature of the beast of where we live,” Rose says, adding that his children sometimes access the internet from the downtown area because downloading and uploading at their home can be hit or miss.

Overall, Rose says feedback about the hotspot program has been positive. “We solve problems,” he says, “and connect programs with people who need them.”

Explore More on

Features

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE