The global demand for cacao, the key ingredient in chocolate, continues to rise as millions of people indulge in their favorite chocolate delicacies. But behind the sweet indulgence lies an agricultural industry facing significant challenges due to changing climate, a shrinking workforce, and plant diseases.

On top of this, there are gaps in scientific understanding of cacao biology, particularly regarding wild cacao pollination, and that understanding may be important in ensuring the sustainability of cacao production.

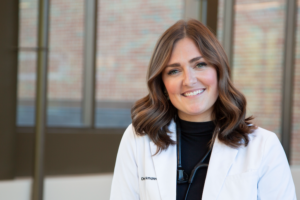

“Considered together, these factors mean chocolate is at risk,” says Holly Brabazon, a doctoral student in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology. Brabazon is collaborating with mentors at UT and Mark Guiltinan, a globally recognized cacao researcher at Penn State University, to learn more about the evolutionary history of cacao, using modern genetic tools and approaches.

A Foundation for Cacao’s Future Begins Here

Supported by the US Department of Agriculture National Institute of Food and Agriculture, the research team plans to use genetics to identify how pollinators interact with wild cacao and study the biodiversity of insects found in and around cacao agroforestry. While she works to address this gap in scientific knowledge, Brabazon is developing data that she hopes can be used in the future to learn more about cacao, increase the sustainability of cacao production, and thus preserve the chocolate we enjoy.

The project focuses on the Criollo variety of cacao, which is often referred to as the “champagne of chocolate” due to its unique, mild and creamy flavor. “Criollo cacao is rare in cultivation and can be difficult to grow,” says Brabazon, “but it is a cacao with a unique background that is important to the history of Central America.” Previous studies hypothesize that these trees are descended from cacao planted thousands of years ago by the ancestors of the people living there today.

Brabazon’s studies of Criollo cacao are being conducted at the Belize Foundation for Research and Environmental Education, a biological research station in Belize. The foundation’s mission is to conserve the biodiversity and cultural heritage of Belize. The entire 1,153-acre property was thoroughly surveyed to locate and map all the wild Criollo trees growing on the site.

“We are grateful for the help from many people living and working in southern Belize. Without their contributions, we would not have been able to visit the hundreds of cacao trees at the foundation to collect leaves for DNA extraction and sequencing,” Brabazon says. She will use genomic tools to study patterns of parentage and how pollinators move pollen among wild cacao trees.

Pollinators are important contributors to both natural and agricultural ecosystems, and Brabazon expands on how cacao is pollinated. “Cacao requires insect pollination. It is primarily pollinated by tiny midges, but the full range of insect species involved in cacao pollination remains unclear,” she says.

The research team is addressing this knowledge gap by collecting and identifying suspected pollinators found on and around cacao flowers, using handheld insect aspirators and handmade sticky traps. Insect net traps were also employed within cacao agroforestry orchards and wild cacao rainforests.

Additionally, the team is analyzing possible environmental DNA or “eDNA” left by pollinators on whole flowers. “Sometimes organisms leave traces of their DNA or cells behind on surfaces, like leaving behind a fingerprint,” Brabazon explains. “We want to sequence the trace DNA left behind by insects that visited these flowers and use that information to infer pollinators.”

“Knowing which insect species are pollinating cacao can inform future work to improve pollinator habitats,” shares DeWayne Shoemaker, department head and professor in the Department of Entomology and Plant Pathology and one of Brabazon’s mentors.

Bean to Bar:

The Largest Class in Herbert History

In an effort to connect students to the world of cacao, Shoemaker teaches Chocolate: Bean to Bar. It’s the largest single course in the history of the Herbert College of Agriculture, with more than 500 students enrolled during the 2024 fall semester. “Everybody loves chocolate,” Shoemaker says in recognition of students’ excitement around the subject.

Brabazon is the lead teaching assistant for the course and helps educate students about the entire process of making chocolate, from growing cacao on farms to producing chocolate bars. Students have opportunities to taste a variety of chocolate throughout the semester and learn about the complexities of cacao production, cacao pollination, and environmental challenges associated with its cultivation. The course also fosters student discussions about sustainability and agriculture.

Brabazon says she wants her work to highlight unique and important cacao diversity. “I am passionate about biodiversity, and I am excited to be contributing to the foundation needed to preserve the biodiversity of chocolate into the future.”

Explore More on

Features

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE